Ron's Story

UNO, Mandeville, Yucatan: 1982-1991

Chapters

Mandeville |

UNO & Yucatan |

David |

Innsbruch |

Divorce |

Cellie's Death |

Yucatan Hydrology & Geochemistry |

Marriage |

Mandeville

Cellie had several pieces of property on the east end of the Mandeville lakefront: one house (1635 Lakeshore Dr., built in the mid-1950s by Uncle Clay for the Prieto family) that she used herself when in Mandeville, a second house (1623 Lakeshore Dr., built in the late-1930s by my Grandfather Ernest) used for rental purposes, and a large vacant lot in the 1700 block near the harbor. The rental house and the empty lot backed up to swamps, forming the floodplain of a small tributary bayou flowing between them into Lake Pontchartrain. More than 20 years later, adjacent "unraised" houses broke up and floated into these swamps and disappeared (sank) during Hurricane Katrina.

Uncle Clay remained a good friend, until he died in 1987 at the age of 80. But the friendship did not extend to two of his three children: Cousin Ernest and Cousin Mary. I remember riding with Uncle Clay in his pickup truck to view family land and we stopped to pick up his son. The feeling of hate from Ernest when he saw me in the front seat could be cut with a knife. Ernest was a volatile attorney and would regularly tell me to leave his law office if I presented an opposing viewpoint. In the process, if he felt seriously annoyed by my obstinance, he would chuck a pencil or pen in my direction. Cousin Ernest had a lot of pencils and pens (LOL) and eventually said he would only work with me when the "Mountain came to Muhammad", but the Mountain never came. Years later, he once needed my support in a family partition of marshland and sent word "Muhammad is coming to the Mountain." As for Cousin Mary, one of the first statements she made to me after I came back to live in Mandeville was she was going to sue me for family obstruction. I had refused to go along with a family sale and Mary was infuriated. Dealing with those two was going to be interesting over the next 30 years.

The Mandeville lakefront lot had originally been filled in 60 years earlier with fill from the dredging of the nearby bayou harbor. Since then cypress trees had grown but the back was still a swamp (now owned by Marilyn and Lloyd). And the area of the house footprint needed fill because of potential flooding from hurricanes. I hired a local with a bulldozer to clear that area and a dirt contractor to bring in clay for fill. Clearing and filling might require approval by the Army Corps of Engineers, depending on the City's agreements with the Corps in 1982 and if the 40 by 50 foot house site was classified as wetlands. We asked no questions and did the job quickly. Being an environmentalist, I felt guilty about disturbing the natural state but we left everything else untouched, including 6 large cypress trees between the house site and Lakeshore Drive. I hand dug trenches around the cypress trees and they did well. Louise and I then drew up house plans, found a draftsman to draft it to building codes, and hired Maranatha Builders, a local company run by Billy Rosevalley, to build it. The house resembled a two story Swiss Chalet resting on pilings 10 feet above a 12 inch thick reinforced concrete pad. Hiring Rosevalley turned out to be a mistake. I watched the subcontractor (out of Lacombe) drive 30 foot pilings (of longleaf pine) down 20 feet. It took less than 10 hits to drive each piling because of the uncompacted nature of the dredged harbor fill. The house would float on top of the pilings with everything tied together at ground level by the concrete pad and above by beams on top of the pilings. Ten years later we discovered the pilings were not pressure impregnated with creosote, only dipped (LOL), and were slowly rotting above the ground water table. I don't know if Billy was aware of the deception because he had already paid the ultimate price by dying of a heart attack, and the crooked Lacombe subcontractor had gone bankrupt. The pilings were replaced by steel columns.

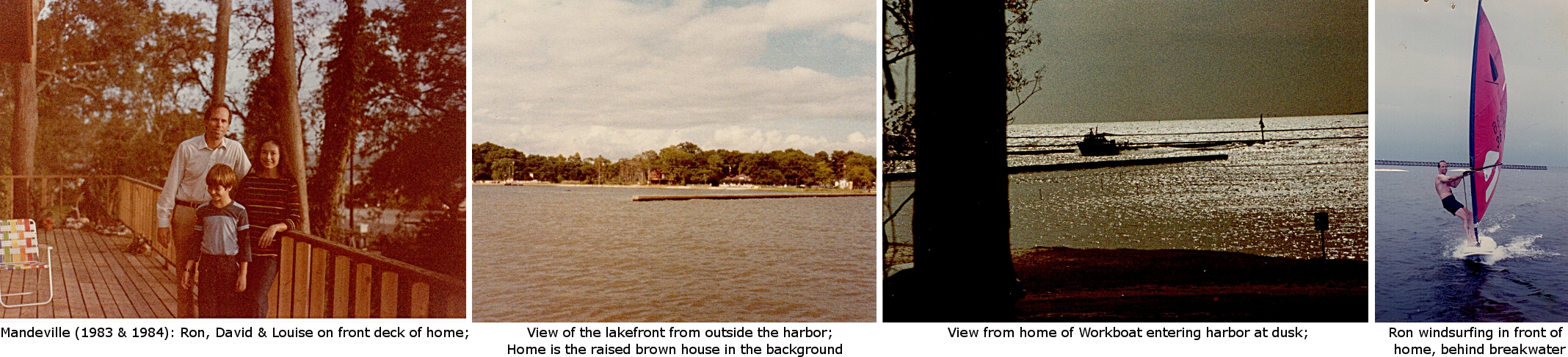

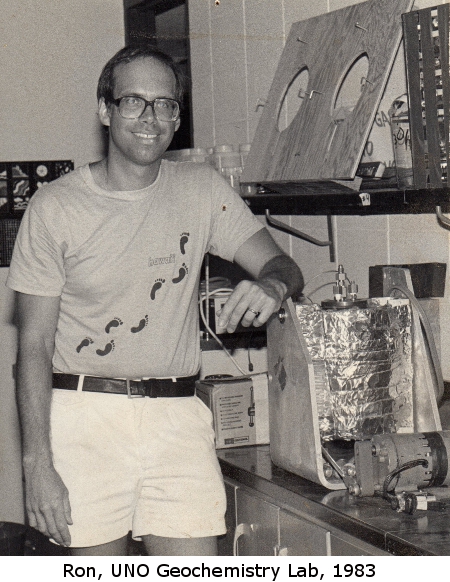

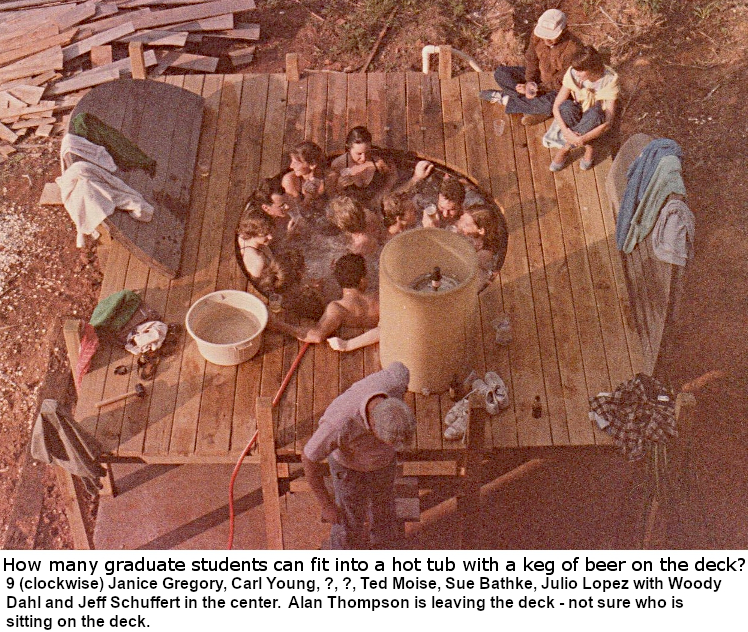

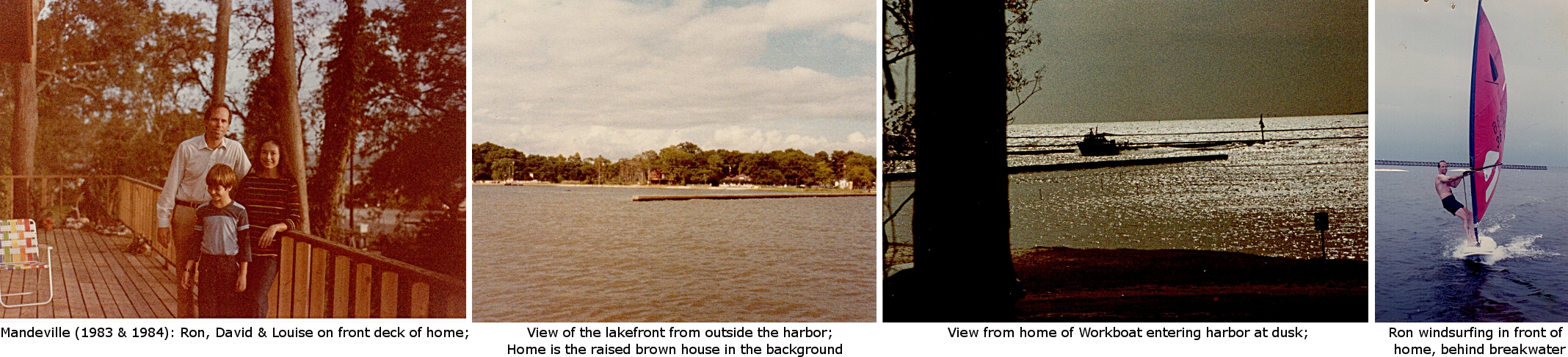

Our house was completed in 1983, and I rebuilt the Baton Rouge wooden hot tub behind the house. The photo to the right shows a graduate student party with a beer keg on the hot tub. Shell geologist Alan Thomson is standing on the deck stairs and the graduate students are feeling no pain - actually Alan isn't either. The location and views from the house were wonderful. The photo below left shows us on the main front deck with cypress trees in the background. The next one was taken from a sailboat in Lake Pontchartrain, showing a Bayou Castine harbor jetty and the shoreline near the harbor. Our raised house (brown in color) is in the center in the "far" background. Other photos show the view from the house: one showing an oil company work boat entering between the harbor jetties at dusk and one of me windsurfing in front of the house. I really loved windsurfing, the feeling of being at one with the water and the wind. However, I could never completely master the quick turn (jibbing) with the wind behind the sail - which takes real skill to stand on the board while the sail swings completely around the mast. Behind me on the board, you can see Uncle Clay's infamous breakwater, his monument that I intended to blow up before I die. Ah, I had such great potential in demolitions but age has slowed me down. That damn structure will outlive me until sea level rise covers and drowns the town of Mandeville.

Return to Top

UNO & Yucatan Research

At UNO I settled in to teaching and doing my research. Initially, I had two geochemistry courses at UNO: A beginning one and an advanced "research-grade" course dealing with classical thermodynamics applications in low-temperature geochemistry. Among the department's graduate students, with some notable exceptions, e.g., Jeff Schuffert and Chris Caravella, there just wasn't enough interest in thermodynamics to support the advanced course. And as interest switched to the environment, the geochemistry courses were replaced with courses in environmental geochemistry. In addition, I often taught Physical and Historical Geology. At this time, a full teaching load was two courses per semester, double the load at LSU and other major universities. My publishing continued and UNO granted tenure and promoted me to Associate Professor in 1984.

The northern Yucatan has no rivers flowing to the sea. The underlying carbonate rock dissolves easily so that rainwater percolates down into a slighty saline freshwater lense, creating a surface topography of cenotes (sinkholes) that are connected by caves. I wanted to start a geochemical water sampling program from the interior to the coast to detemine quantitatively the chemistry of the water-rock reactions.

Back at UNO I started working with Alan Thomson, the Shell geologist known for his work on the importance of secondary chlorite in preserving porosity and permeability in the Tuscaloosa sandstone reservoir. Alan was a character, full of stories of a lifetime of geology. One story I remember in particular of he and a friend driving across west Texas and a buzzard crashed through the car's windshield, landing in the lap of his companion. I had published my regular solution chlorite model in Clays and Clay Minerals in 1984 and wanted to model chlorite formation in reservoirs. My first M.S. graduate student was Elizaeth (Beth) Alford who examined changes in chlorite compositions and polytype as a function of reservoir temperature and pressure in the Tuscaloosa Formation. Beth was very smart and very beautiful, so much so it made me nervous to be around her. (I can admit this 35 years later! (lol)). I arranged for her to go to Californai to use a microprobe to analyze the chlorites. I didn't realize at the time, but sending Beth to the West Coast irritated Skip Simmons to no end. Skip is an excellent petrologist (now retired) who had set up a microprobe from the University of Michigan. He took my action to mean that I didn't think the UNO microprobe would provide as accurate results, which at the time was probably true. At Beth's thesis defense, he racked her over the coals before we passed her. It was the first defense that I chaired and Skip (who is very likeable) caught me by surprise. After that, I was careful to never let another faculty member take out their anger on one of my students at their thesis defense. Years later, I replaced a professor whose personality problem with my student stemmed from a disagreement with the student's husband, who had been a UNO graduate student. The professor questioned my authority to remove her (LOL). I was not going to allow someone to bully my student. Beth worked as an oil industry geologist but later changed fields, becoming an attorney. And I have lost track of her.

Geochemists were attempting to predict the movement of aluminum released during the transformation of aluminum silicates in sandstones during sediment burial. If aluminum was mobile than secondary porosity could incrase permeability in these rocks, making them better petroleum reservoirs. Unfortunately, the solubility of aluminum is generally a close approximation of zero in aqueous reservoir fluids, i.e., below detection with flame atomic absorption, arguing against significancnt aluminum mobility. Ron Surdam soggested a way out of this dilemma. He proposed that aqueous aluminum bonding with aqueous organic complexes, present in reservoir fluids, would dramatically increase the aluminum solubility and published supporting experimental results. This was the new "hot" topic in geochemistry and was another Lynton Land moment for me. Accurate alumunum analyses are difficult and the high aluminum analytical results in Surdam's paper didn't follow common sense. For example Surdam reported an experimental water rock ratio of 1000 to 1, which meant total dissolution could only produce a 1000 ppm of dissolved elements. Yet his measured aqueous Al concentrations alone were already of that magnitude without total dissolution. I assumed the aqueous samples were not adequately filtered and solid particles were being analyzed. I tried and failed to show enhanced aluminum concentrations in similar experiments in my labratory. Eventually, Ed Pittman, no longer at EPR but at the University of Tulsa, and I published a critique on secondary porosity in sandstone reservoirs in The American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin in 1990. This once again starting a sequence of dueling papers and talks. At this stage in my career, I was definitely into controversy.

The process of diffusion around dissolving feldspars in sandstone reservoirs could be useful in back-calculating flow rates of reservoir fluids. The released aluminum would both diffuse and be carried away by fluid movement before precipitating as kaolinite, forming a halo around the dissolving grain. The shape of the halo should increasingly move from circular to elliptical with increasing rate of fluid movement past the grain. I modelled the process and published the diffusion/flow results in Geology in 1987, showing halo shapes as a function of the rates of fluid flow. I loved the thought processes used in solving differential equations with finite difference techniques and writing the computer programs. The university computer center was no longer necessary, as the modelling was done on a desktop PC. Sometimes my PC would run nonstop for a week at a time. My enduring sadness is not having been more serious in undergraduate math courses. My math background was not good enough to easily advance to using finite element techniques in numerical modelling. Only after math became useful in my research, did I truly appreciate its power. Willard Gibbs famiously said at a Yale faculty meeting (to counter liberal arts professors who emphasized language studies) "Math is a language." I'm told that could have been his longest statement at any faculty meeting (LOL). And math, like any language, has to be used to both appreciate and master it.

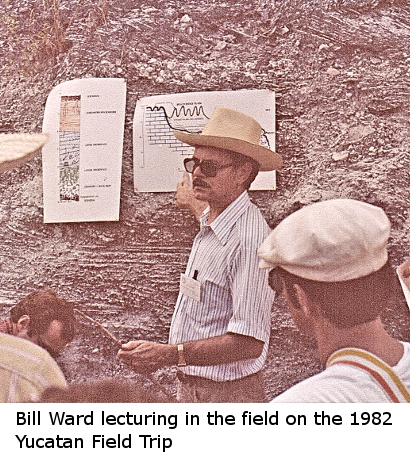

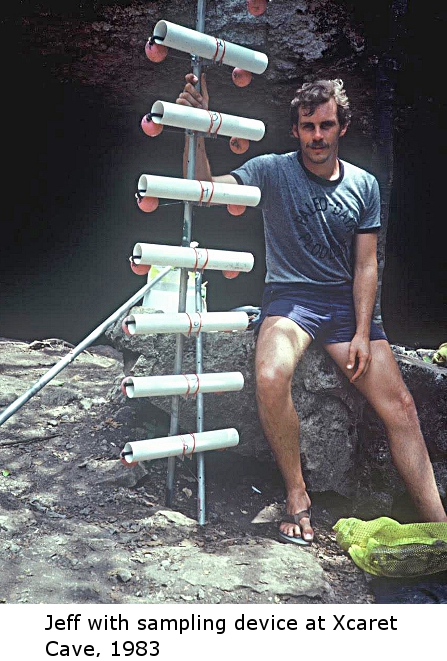

Jeff Schuffert was in my first geochemistry class. He and I started the Yucatan work on the coast. He was brilliant and left before graduating to go to Scripps for his Ph.D. where he worked for Miram Kastner. Jeff never turned in his M.S. thesis to graduate but that was probably my fault. He did good geochemical research in the Yucatan. Eventually in 1988, we published our coastal mixing zone results (Jeff, Bruce Ford - who was a later graduate student, Bill Ward, and myself) in the Geological Society of America Bulletin. This was the first of a number of papers on the Yucatan. When Dale Easley, a geohydrologist joined the UNO faculty in the late 1980s, his graduate student Yolanda Moore added water flow measurements to the ongoing research.

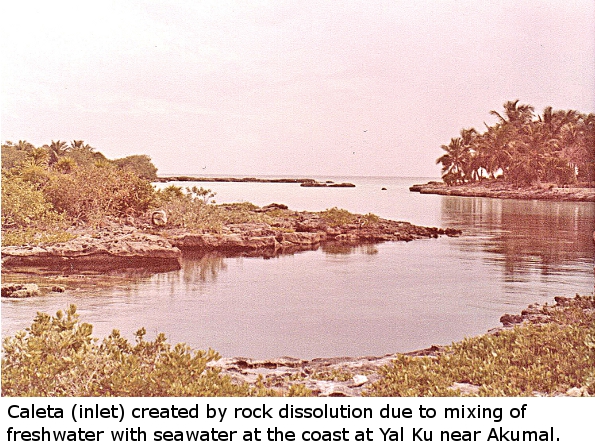

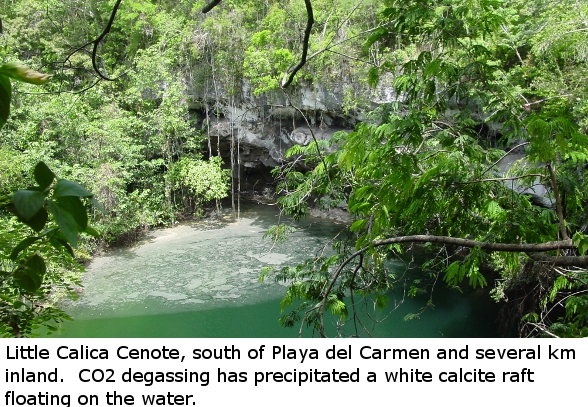

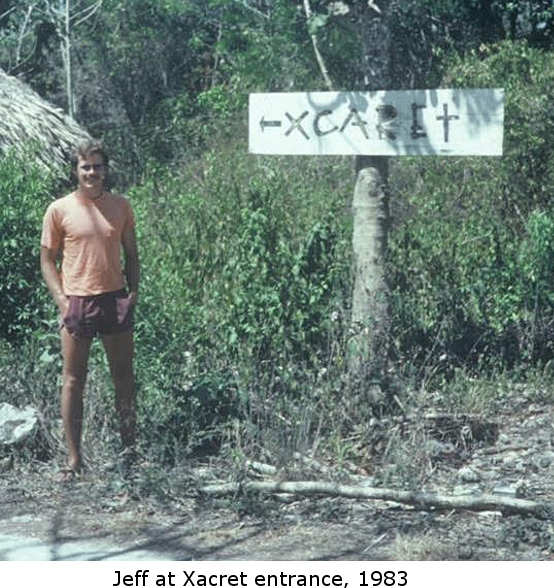

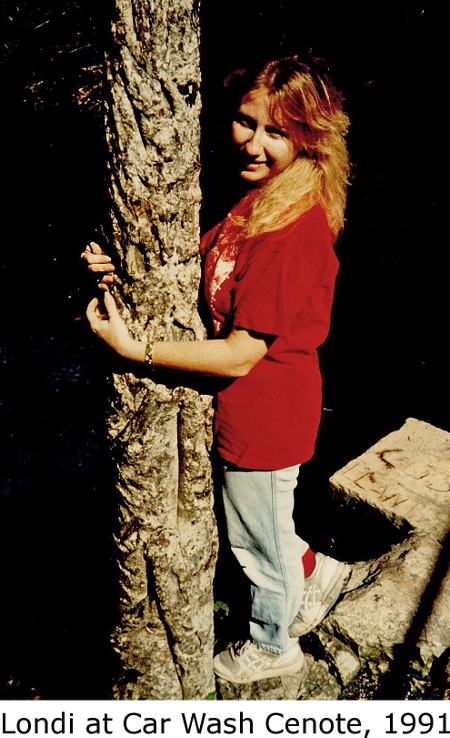

This paragraph summarizes the geographic scope of the field geochemical and hydrological work in the Yucatan done over the next 20 years (1983-2003). The mixing zone (overlying freshwater with underlying seawater) water chemistry and flow measurements began initially at the coastal cave and caleta at Xcaret (south of Playa del Carmen) and at the Yal Ku caleta (just north of Akumal) with Jeff's work in 1983 and extended south to the cave and lagoon at Tankah (Bruce Ford's work in 1984). Tankah is just north of Tulum. After that in the early 1990s we moved inland a few kilometers from the eastern coast. Lauren Marcella, Londi Moore (Dale Easley's student), Yong Chen and I worked with the Calica boreholes (inland from Xcaret) and in various sinkholes, including Big and Little Calica Cenotes, Cenote Chemuyil, Maya Blue Cenote and its cave, Temple of Doom Cenote, Car Wash Cenote and its cave, and the beautiful Cenote Angelita (south of Tulum, initially called Cenote Linda) and Cenote Azul further south near Chetumal. Woody Dahl, another UNO graduate student (but not in geochemistry) helped with the initial field work. I think Woody liked resort work (lol). Yang Chen helped Yong in the field with his research. Yang meanwhile was doing a labratory simulation of high-Mg calcite diagenesis back in the UNO Geochemistry Lab for his MS thesis. Jim Coke, the legendary Yucatan cave diver assisted when we needed help. In 2003, Jim Coke and I (along with Cajun Louisiana soil scientest Arville Touchet) sampled interior cenotes across the Yucatan, first from Playa del Carmen down to south of Tulum and then westward to the Bay of Campeche. These cenotes included Laguna Chumkopo (south of Tulum) and Uzil, Xcolak, and Sabak-Ha (all in the interior) and Santa Rosa (near Celestun by the Bay). Coke was younger than me and I just learned (February, 2017) that he died the previous year. Now there is no one left that I worked closely with all those years in the Yucatan - makes me feel a little empty.

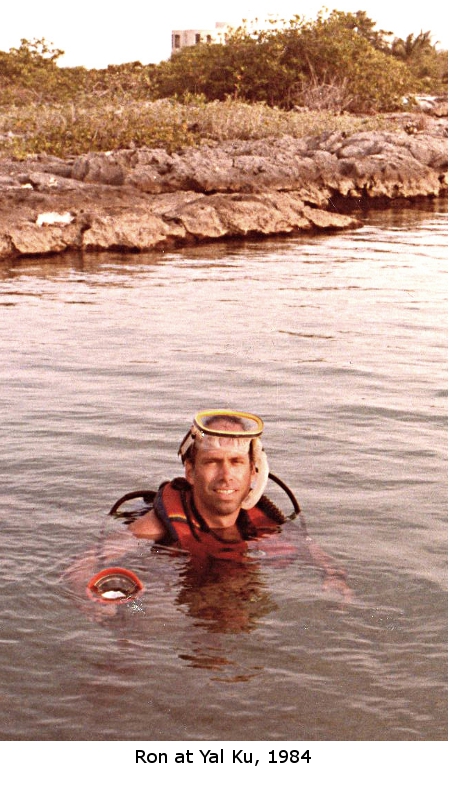

Jeff had built a sampling device of pvc tubes mounted at right angles on a pole in which the open tubes could be shut simultaneously while holding it in a vertical position from the top. With Jeff, this device was used at the cave mouth at Xcaret and where the freshwater entered the caleta at Yal Ku. The Yal Ku Caleta is beautiful and we swam it often with scuba gear, followed closely by barracudas, making sure we wore nothing flashy to cause an attack. The beachrock at Yal Ku contains embedded beer bottles, showing how fast carbonate cementation can occur. This area was a favorite stop for geology field trips from the States to illustrate the process of beachrock formation.

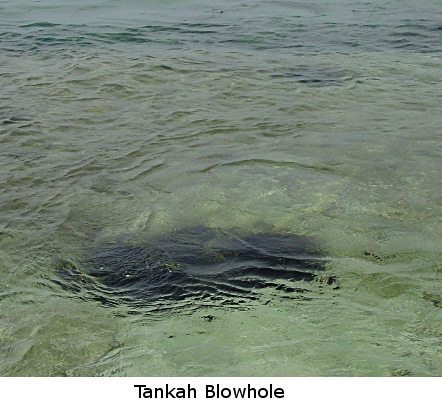

Bruce Ford used Jeff's sampling device in 1984 for sampling at Tankah at the mouth of the submarine cave leading out to the Caribbean Sea. Now that was a dangerous cave to swim. In other areas we would free dive or scuba dive down to take single samples. In later years at the inland cenotes, we used a stainless steel open tube dropped on a cable from the surface and closed with a messenger to sample at different depths, working from shallow to deep. Eh, pH, conductivity, and water temperature were field measured at the sampling sites. Initially, this was done on the retrieved samples but later we had probes to make depth profiles of those parameters before sampling. The bulk water samples were taken back to our lodging which was generally at Akumal. There the samples were filtered, alkalinity and sulfide titrated, half the aliquots acidified with HCl, and the bottles sealed for complete analyses back at UNO. Rock samples were collected from the wall rock adjacent to the sampling depths, in order to relate the fluid chemistry to what was happening in the rocks. At the halocline or mixing zone between the overlying fresh water and underlying seawater, the underlying seawater was significantly warmer than the freshwater and the halocline looked like a thick layer of glycerine. The halocline was a zone of carbonate rock dissolution, so it was generally marked by a dissolution notch, cut in the adjacent wall rock. In the deep inland cenotes, we would later find a sequence of these notches, marking the halocline locations when sea level had fallen during the Ice Ages and then stabilized.

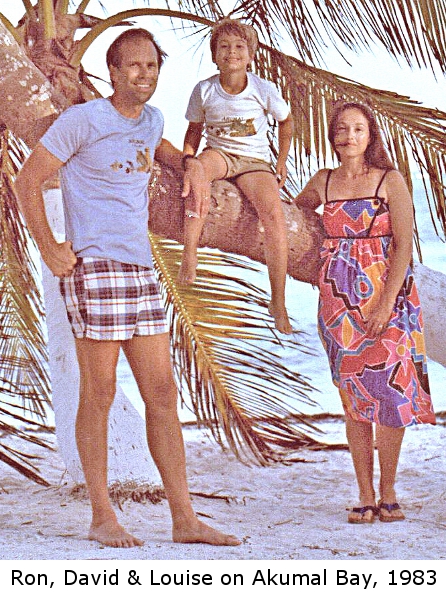

Louise and David often came on these trips to stay in Akumal on the beach. In the early 80s we stayed at Las Casitas which sat on a headland separating Akumal Bay and Half Moon Bay. Akumal is a Mayan word for turtle. The sea turtles crawled up at night on the beach to lay eggs in the sand and then covered them up in nests, before slipping back into the Sea. The sand was soft, composed of bits of aragonite shells, light brown in color, and the Caribbean Sea was green and beautiful.

The UNO paleontologist Kraig Derstler came on one of the trips in the early 80s. Amazingly, Kraig could not swim. He was a "sinker". No Problemo, scuba divers wear a BCV (buoyancy control vest) which is a life jacket that can be inflated and deflated using the scuba tank and an outlet valve. So we strapped on our scuba gear and went out into shallow Akumal Bay behind the outer reef to observe and attempt to catch lobster hiding in the patch reefs. Kraig was like a dancing manatee with that BCV on! We went all around the bay area and lost track of where we were. Eventually we rose to the surface. Wow, we had gone through a hole in the reef and were outside it in the open sea with big waves. We dropped down 15 feet to the bottom to swim back. But there was something seriously wrong. No matter how hard we swam, the coral next to us remained in the same position, i.e., we were not moving. We were in a rip current coming through the reef hole. I wasn't sure what Kraig thought about our situation, but I was worried. Kraig suddenly rose to the surface and I followed. He swam to the reef, climbed up and started crawling across it (about 50 feet in width at this point). "Christ", I thought, "He will rip his skin to shreds on the coral." But what to hell else could we do? I followed and we were both a bloody mess when we crawled up on shore. Later, I would recount this story when teaching about the danger of rip currents in freshman physical geology.

Meanwhile I had been working on the use of stoichiometric saturation to explain Br partitioning between precipitated halite (NaCl), sylvite (KCl) and brines. This concept predicts the precipitated stoichiometric (actual) solid solution composition will always be in equilibrium with the aqueous solution but not necessarily the end member solid components of the solid solution. Given time and reaction kinetics, the solid solution than slowly recrystallizes in the presence of the aqueous solution to reach true thermodynamic equilibrium. It is an interesting concept explaining the initially high Br contents in halite precipitated from evaporating seawater to the actual Br content found in recrystallized halite in deep subsurface reservoirs. Alden Carpenter and I published my stoichiometric saturation computations in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta in 1986, followed by a response in the same journal in 1992 to a later criticism by Glynn. The concept is not without controversy among geochemists, but there are numerous analogs of the stoichiometric saturation process occurring in the precipitation of solid solution minerals in nature, e.g., high Mg calcite converting to low Mg calcite.

At this time, I was also working to extend Guggenheim's quasi-chemical model for clays to more accurately compute the entropy of mixing when there were significant site interactions. The model derivation was complex and done on long walks on the Mandeville Lakefront, listening to waves crash against the sea wall and playing with the computations in my mind. This was the closest I ever got to doing "rocket science" (LOL). The model was called the quasi-lattice model and was eventually published in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta in 1989. Although I continued to delve in statistical thermodynamics, this paper represented my limit, given both my mathematical ability and background. I had always loved being outdoors doing field work and more and more my future research was built on data taken in the field, followed by labratory and computer analyses. You know the saying "You can take a boy out of the country but you can't take the country out of the boy." And so it is with field work for a geologist. I never met a research geologist, no matter their speciality, who did not love being in the outdoors taking data. It's in our DNA.

Return to Top

David

Throughout this time, Louise was working for the state as a psychologist at Southeast Louisiana Hospital. She and David would come with me to my academic conferences if they were held in interesting places, e.g., San Francisco, Colorado Springs, Miama. And David was growing up quickly. As a child he was somewhat introverted, a little chunky and didn't realize how good-looking he was, so his self esteem wasn't great. He had two parents with Ph.D.'s who expected academic excellence. His "modus operendum" was to make the Honor Roll by expending the least amount of effort as possible, i.e., cut it as close as possible and consequently sometimes not make it. This was David's approach to school all the way through his first 2 years of college, before entering the Air Force which changed his attitude.

David liked soccer but he was a thinker, sometimes debating within himself if he really wanted to run up and kick that ball (a not so useful trait in sports, but great for survival - "think before acting"). As a child he liked to climb up on my back while I did pushups. He also liked to crawl up our stairs to the 3rd floor at night where I would be working on the computer, looking out on the darkness outside and the lake. Suddenly, I would feel something grab my feet, scaring the hell out of me. But years later I got my revenge, tossing pitchers of ice water on him when he was in the shower (lol); that is, until he started to reciprocate. We were sometimes "partners in crime". One Fourth of July afternoon, David and I were sitting on an upstairs deck, shooting bottle rockets at the roof of my neighbors house which sat across an empty lot and a small bayou (Little Bayou Castine). The occupants were Cousin Joan's family and they were firing back. But we held the high ground and their fire was largely ineffective. They (I think) called the police because Officer Floyd drove up. Office Floyd had just been hired and told us to cease and desist, that shooting fireworks was illegal in Mandeville. He then drove off. Out of respect for the law, we waited a couple of minutes before finishing the bombardment with a grand finale of a blaze of rockets. And over the years, Office Floyd became a good family friend. Thinking back on this incident makes me realize I was perhaps (lol) not entirely guiltless in the bad relations that existed with Cousin Joans extended family. Her brother was Cousin Ernest and her sister was Cousin Mary.

I think David had the potential to set the record for attending the largest number of schools while living in Mandeville. His public school career at Mandeville Elementary on Monroe St ended abruptly with the second grade. He had a bad teacher who disliked him (too white for her taste). When we found out she would also be his teacher in the third grade, we pulled him and sent him to St. Paul's Catholic School in north Covington. It was a good school, originally established in the 60s to escape public school integration. He had to ride the bus each day and I remember running out of gas one morning, a block from the bus stop. I looked at David and he knew what was coming. He climbed out the passanger seat while I shouted "Run David Run!". We still laugh about that today. By the time David was to enter junior high, we wanted him to have a better academic background and transferred him to St. Martin's Episcopal School in Metairie across Lake Pontchartrain. By this time David was going through puberty and developed discipline problems in the 8th grade, mostly (I think) as the result of my pending divorce with Louise (another story). In the final incident in 1991, a school friend of David, underage for driving, had driven his mother's BMW from Metairie, across the Causeway to Mandeville. He picked up David and they bought a case of beer. David, now driving, did not know how to turn off the bright lights on the vehicle and they were stopped by officer Floyd. At the station he and his friend were fingerprinted and had their mug shots taken, before being released into our custody. Floyd was attempting to scare the two boys into changing their ways. It turns out it took more than that incident for David to "shape up."

So what could we do about getting David to change his ways. We sent him in 1991 to St Stanislaus, a Catholic Boarding school for boys on the Mississippi Gulf Coast in Bay Saint Louis. The school is well-known for tough discipline and dealing with tough cases. I later discovered his roommates had extensive rap sheets and were there to avoid reform school. One of these roommates was from Mandeville and eventually ended up getting his pilot's license, achieving his lifetime goal of flying drugs from South America to the Bahamas. At the end of his first year at St. Stanislaus, David persuaded us he had mended his ways and we let him transfer to Mandeville High School, which actually was a move for the worse. The school was the ultimate party school, full of rich kids who had never worked for anything. Years later David said most of his former friends had become losers, spending their adult years on drugs and still working as bartenders, waiters, and waitresses. I remember once hiring David and his close friend Ryan McClendon (partners in crime) to move concrete blocks on a construction site. Wow, did they have a lot of energy and were so happy! I now know they were both on LSD! But David survived that stage, as I will tell later! He turned out great and is a consulting engineer today. But it was a scary time for Louise, for me, and for his stepmom Londi who gave up her career as a geohydrologist to shepherd him to adulthood.

Return to Top

Innsbruch

UNO ran a wonderful summer school in Innsbruch, Austria. The Innsbruch University on the Inn River rented out classrooms and dormitory space for the UNO students while the summer school faculty rented apartments in the City. Innsbruch (Tyrol) is not like Bavaria with "friendly" locals but more like Appalachia with "suspicious" locals. I remember a well-dressed, genteel-looking older lady shoving David off the sidewalk as she walked by. He was in her way. On my first time teaching at the summer school, the landlady must have violated a protocol by renting to foreigners. If the house gate was left open, we would be blamed. This was irritating to me and one night, we came home and I was decidedly drunk. I opened the metal gate and "for good measure" loudly slammed it shut, rattling the house. The gate fell apart, must have been made in Thailand. Lights lit up the apartment house, and we hurried to our apartment. There was a knock on our door and this guy is standing there, shaking his finger at me, saying "Bad, Bad Boy!" He was quite the gentleman, I thought. I grinned back at him. I really loved being in the Alps.

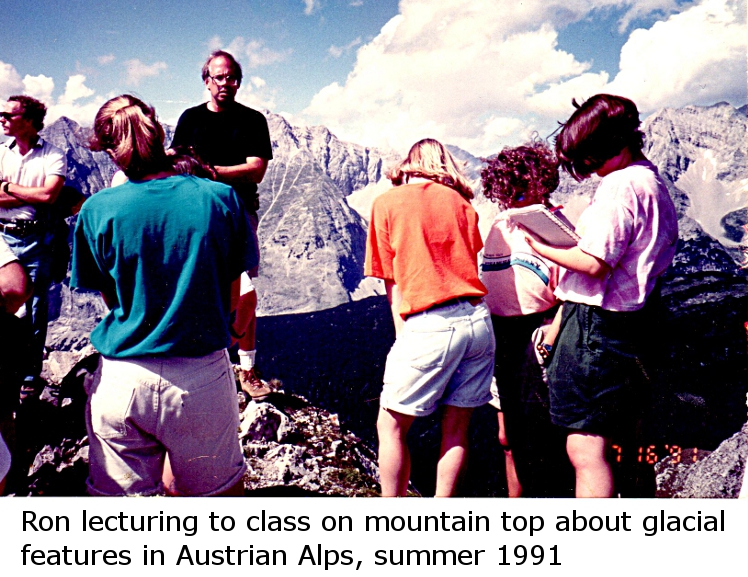

The summer school students came from universities all over the United States, mostly rich kids who could afford traveling in Europe. Those from UNO were usually on scholarship to cover the costs. The Austrian Alps are not much taller than the Appalachians and are composed of "mundane" grey limestones but are "oh" so beautiful. Being composed of sedimentary rock, the peaks in the Alps are sharp, e.g., the Matterhorn, unlike most American mountains which are composed of crystalline rock and consequently have rounded peaks, e.g., Pikes Peak. My knowledge of the geology of the Alps was limited. But no problem. I followed the time-honored academic procedure, explained to me by fellow UNO faculty member Al Weidie, of gazing profoundly off in the distance, waving my arms, and expounding my thoughts. My classes would ride the ski trams and lifts to the mountain tops to observe glacial-carved features and discuss the formation of the Alps due to the suturing of various subcontinents to the "soft underbelly" (totally inaccurate, but great term) of Europe. We also had this cool field trip in which we hiked up to the top of a glacier on the Italian border and collected red and yellow garnets that had weathered out of the bedrock. The students were good natured but not motivated to study. Their goal was to tour Europe on the weekends, not to spend time studying or sitting in classes. Once, on the glacier, a Japanese-American student and I observed an apple-size yellow garnet, on the ice, at the same time. The student had already told me he wasn't going to take my tests and would not report his failing grade to his university ("ungrateful kid", lol). As he reached down for the garnet, my old "Mardi Gras instincts" kicked in. Instinctively I raised my foot, ready to obliterate his hand, when reality struck me. This was not a Mardi Gras throw but a treasure he would keep to remember this summer for the rest of his life. And he left with both the garnet and his hand. I was such a softie back then.

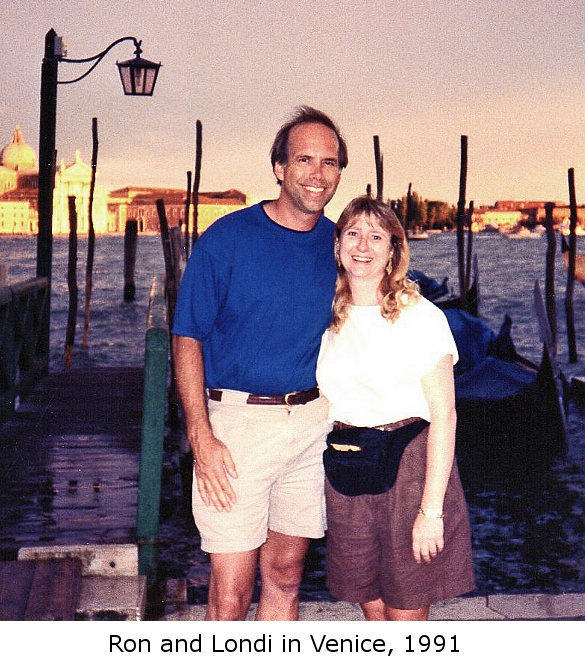

We also traveled some at the end of each summer school before heading back to the States. David, Louise and I toured Italy and Southern France with Venice being the high point of the summer in 1986 and Londi and I toured the French Alps (prior to summer school), Vienna (during summer school), and the Swiss Alps (after summer school) on the second trip in 1991. (On that trip, David had left us early to go to an Outward Bound Camp back in the States, as punishment for being a juvenile delinquent at St. Martins.) On the first trip David was already old enough to want to party with the students, and they would buy him beer. I have this crazy memory of David in a beer hall in Munich, being chased around the long wooden tables by his mother Louise while he waved a stein of beer in the air. He would have been 9 years old in 1986. We, of course, cheered him on much to the exasperation of Louise. But I don't think she was really mad! We start drinking young in South Louisiana.

At the end of the 1986 summer school session, we drove to Venice where a pigeon spent the night, determined to peck his way into our room overlooking a canal. David spent an hour the next day standing in St Marks Square, covered from head to toe in pigeons, pretending to be a statue for the tourists. Then we drove to Florence (with its incredible museums) and finally to Rome. Rome I could have skipped. Yes, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was impressive with God reaching out to bring life to mankind (a worthwhile endeavor? - debatable, given the present state of Earth). But leaving the city was so difficult. I was so lost, circling endlessly in roundabouts in which no Italians obeyed traffic signals (not in their DNA). From there we went to Piza to climb the leaning tower (where I tried unsuccessfully to persuade David to jump to test Galileo's obsevations) and on to the French Rivera at Cannes so I could attend a Penrose Conference (and write off our tour expenses). David couldn't get over all the topless women, sunbathing on the Mediterranean beaches. It was hard to keep the boy under control. Being short on cash, I introduced him to that delicacy of stewed cow's tongue in Cannes and he didn't know what it was. He has never forgiven me. It wasn't until he had nearly finished his meal that he noticed the distinctive tongue pock marks on the edges. Later, I tried him on calf's brain but he wasn't impressed. Brain does have a unique sandy, gritty texture that is not to everyone's taste.

From Cannes we drove north, following the pinot noir vineyards in the Rhone River valley of southern France. (I love drinking French pinot noirs with their rich velvety flavor, the one wine grape that California has difficulty matching.) At one point we stayed in this beautiful, romantic little inn with cherry trees blooming outside our window. I remember Louise needing ice, so she and I went to the lady at the front desk and asked in English for ice. The desk lady just stared at us. She must have been practicing that dead-pan look on Americans. Louise was of French ancestory and knew some Cajun French. So, she tried to ask for ice in French. Same response. Almost all the inn guests were Americans, so the lady had to speak some English. I looked at her, making eye contact and then back at Louise, saying loudly. "Baby, you know how bad the French education system is. You can't expect a country woman to know English." I looked back at the desk lady who stared back with her dead-pan look, before grinning and saying in English "I'll get the ice." (lol) It is funny what we remember from our trips.

Return to Top

Divorce

This is the part of my life that I have to tell honestly what happened and is the hardest to write about. Louise was the most beautiful woman I was ever with but we were not destined to spend our lives together. I was more married to science than to her, and science was no longer enough for me. I needed a woman to do things with. I loved being in the outdoors but she hated the outdoors. I loved hiking and she hated the thought of exercise. Living in Kenya in the Amboseli Game Park, back in 1975 where I did my Ph.D. field work, had been the most exciting time of my life. I thought Louise, an experimental psychologist trained in animal behavior, had also enjoyed that experience. Louise now confided that she hated being there, living under "primitive" conditions at Ol Tukai. We did not enjoy doing the same things and had grown apart with many verbal arguments. Our relationship wasn't close and I was unhappy with my personal life. I needed more, and unknown to her, had been unfaithful during our marriage. Then, in the spring of 1989, I met Ida, a younger UNO professor in another department. She was a fascinating, intelligent woman who showed me the wonder of a truly intimate relationship. It is a self-serving statement for me but she once said "I don't feel guilty because you are not happy in your marriage." And that was true. Although our relationship didn't last a year, we have remained friends. A few years later after she was promoted to Research Professor, she pushed me to apply and be promoted also to that position.

The incident that brought everything to a head occurred in late December, 1989, about the time of the "Big Freeze" in the "Big Easy". Louise went on an overnight trip. David and I were bacheloring together in the Mandeville house. My mother Cellie had moved from Crowley to Mandeville and now lived just a block away in her lakeside home. She was 80 years old and had become increasingly frail. She could only play the piano with one hand, having lost much of the use of her left hand, only able to move it as a club. And she had real difficulty climbing stairs. We thought it was arthritis, but she was in the beginning stages of ALS and would only live another 15 months. That evening, Cellie was worried about my cooking, and she asked to come over to cook for us. She was there working away in the kitchen when Louise unexpectedly returned. Louise was angry to find her there and told Cellie to leave, essentially throwing her out of the house built with her financial backing on land she donated to me. Her act made me realize all we had in common was David. He was now 13 and the marriage was destined to end soon. Within a month, I told Louise I wanted a divorce, confessed to my infidelty, and moved out first to Cellie's house and then in early spring rented one side of a shotgun duplex in Mid-City New Orleans, not far from UNO.

Alimony was not a possibility for Louise because her salary from the state was larger than mine as a professor. My confession had made her the aggrieved party, and Hell has no vengenance like a woman spurned. Her parents were angry and professed they would try to get land already donated to me by Cellie and also my eventual inheritance of properties from her. Previously, Cellie had donated an undeveloped city block in unincorporated Mandeville to Louise. (Cellie had inherited 20 undeveloped city blocks outside the Mandeville city limits and a few more inside the city.) So I had to prepare for a legal battle. I did not know how my infidelty would affect the legal proceedings. My cousin Marsha Burris Higbee, an attorney in New Orleans, obtained for me the services of her previous divorce attorney, Rob Lowe. I was by then living in New Orleans so I filed in Orleans Parish for divorce based on incompatibility, rather than in St. Tammany Parish, where the extent of my present and future land holdings was probably common knowledge. Louise filed back, claiming infidelty (true), verbal abuse (perhaps true) and physical abuse (not true). In his New Orleans office, Rob Lowe looked over our past joint income tax forms, saying "Okay. The infidelity shouldn't matter, verbal abuse is incompatibility, and physical abuse is commonly claimed, regardless of facts. We have two 'incompatible' professionals, one child, and not enough joint assets to fight over. Split your joint assets and you pay child support." He looked up at me. "You're not holding anything back are you?" "No" I replied. "I have family property by donation but it isn't joint property." Louise hired a New Orleans attorney, a lady who by chance happened to live around the block from my New Orleans girlfriend. Although separated, I assumed I was under surveillance for adultery. But the thought of any court battle disappeared in the first legal session. The judge recognized Rob Lowe and called him to the bench to autograph Rob's book on Louisiana divorce law. Obviously, Marsha had picked the right lawyer for me. In the divorce, Louise received my share of half the house in return for the land she had been given as a donation from Cellie, not a bad deal for her. She also received primary custody of David and child support from me. (She gave up both a few months after the divorce when David moved back to live with me.) And she paid back half of our loan from Cellie used in building the house. Although separated throughout 1990, the divorce was not finalized until January, 1991. And Cellie died two months later, at the age of 81, the last of her siblings. Louise continued working at Southeast Louisiana Hospital until retirement, living in our Lakefront house. We regained our friendship and have kept it to this day. She has never remarried and now (2017) lives in Austin with her boyfriend William Bruce (retired Psychology faculty member from the University of North Carolina in Asheville). They live close to David and his second wife Shelly Moses.

Return to Top

Cellie's Death and Londi's Help

After moving to New Orleans in 1990, I became friends again with Carla Pauls who was teaching special education courses in New Orleans. Carla and I have remained friends but she is a born-again Christian. I think God eventually told her to avoid me for the good of her soul. And Dorothea LaGraff stopped by on her way from West Germany to the West Coast. I was obviously a bad doggie but a happy one.

Cellie's condition continued to worsen, losing more of her mobility. She would not be able to live alone much longer. Doctors had not been able to diagnosis what was wrong and she was turning 81 in 1990. Lloyd and Marilyn wanted me to put her in a nursing home and she agreed. In the beginning of the summer of 1990, I moved her into a Slidell nursing home, 20 miles away. Carla Pauls knew her and came with me several days later to check on her. She had injured an ear drum with a cotton swab and was incredibly depressed, begging me to bring her home. Carla's mother had died of ALS, and Carla mentioned that Cellie's speech was becoming slurred. But she didn't tell me that she thought this was the beginning stages of ALS. I was leaving for San Francisco for 5 days to participate in an AAPG debate on secondary porosity. I promised Cellie I would bring her home as soon as I returned and would set up a home care system for her. It was hard to leave her there, even if it was only for a week. A nursing home is only a place to go to die. We all deserve better. Cellie would die at home.

We needed to raise money to help pay for estate expenses and taxes after Cellie passed. Cellie owned 440 acres north of Lacombe that had been clear-cut of timber 30 years earlier. When walking the land, there did not appear to be much timber that had grown back. A local forester told me it wasn't worth cutting. Londi and I were walking the land one afternoon to check on fire damage, when we met Joey Stringer (a Mississippi logger) who was cutting 40 acres of timber on adjacent land. Joey wanted permission to cross our land to reach the adjacent 40 acres. He was an interesting redneck character who referred to Londi as the "Little Heffer", making her mad as hell and causing me to chuckle. Joey said he was paying the adjacent landowner $10,000 and offered to pay my family $100,000 for our timber on the 440 acres. I ended up selling to him all but the timber on 80 acres which had a temporary legal tie-up. Several years afterwards, a state forester told us he was familiar with our land and thought there had been actually $400,000 of timber on our property. Apparently I was set up by the "local" forester. Turns out that this happens often to landowners. After this, we always paid Bennett and Peters (a consulting timber management company) 10% of the sale price to survey our timber and conduct the timber sale. But there was more about Joey Stringer. He had also dealt with Cousin David Moore on their property, and Cousin David told me this story making the rounds among lumbermen. Joey was away from home and he found out his wife was having an affair at their home in Mississippi. He decided to return unexpectedly and to scare the couple by bursting into the bedroom, firing away with a gun loaded with blanks. And he did this! Turns out the man had his own gun and it was loaded with real bullets (LOL). Joey was shot but lived.

Londi began to help me with Cellie, finding nurses, first to stay during the day in the summer and then in round-the clock shifts, beginning in the fall. And in the fall, we moved from New Orleans to her home in Mandeville to help her. Londi was still a graduate student and we did the daily commute to UNO. At the end of the summer, a neurologist diagnosed Cellie with ALS. He examined her and after she left, pulled me aside to tell me. Later at home, Cellie howled in dispair and cried when she learned her diagnosis. She never cried again over it but asked me, when the time came and she couldn't move, to help her die by suicide. These were not all sad months. She would sit in a chair in the sun out in both the front and back yards with her cat on her lap, watching the world move around her. Her good friend Gail Dale came often. She loved her nieces Cousins Marge and Joan. And Marge came from New Mexico to visit her. But Joan, who lived a block away, never came. I don't think she could face ALS. Marilyn came from Europe and in her usual business-like way fired all the nurses (LOL) before she left. The nurses cared deeply for Cellie and (of course) I rehired them. By winter, Cellie was enrolled in hospice and their people instructed us on giving morphine and other drugs to make her comfortable. The first Iraq war was taking place and she watched the news and loved watching Golden Girls. After losing her speech, Cellie would tap out messages on an alphabet board. When a minister came by, she tapped out for him to leave. Earlier, I had asked her if she believed in God. She said she thought religion was wonderful for the children and that was why we went to Church in Crowley. The end came in early spring on March 5th, a few days after she had adopted her remaining cat to a friend. The previous evening, she had been in discomfort and after clearing her throat with suction, I dripped excess morphine down her throat. She looked at me with her brown eyes as I held her up. I told her that we would be OK, hugged her, and laid her down to sleep. The nurse, sweet Hattie Brown, woke me at 2 AM, saying she was passing. I held her hands, felt her move, and then she stopped breathing. There is a saying in the South, "A Lady knows when its time to go." I had probably overdosed her on morphine a few hours earlier. But I felt overwhelming relief. Cellie was no longer hurting and in dispair and if there is peace following death, she had found it. Writing this 26 years later, still brings tears to my eyes.

All during the previous fall, I (with Marilyn's help) had been working on getting Cellie's estate ready for the irs. Even 26 years after Cellie's death, I hesitate to talk much about this (LOL). I'll say the obvious "You can sometimes hide cash but not real estate from the irs." And our problem was the value of her real estate. Would we have to sell the land to pay the inheritance taxes? There were literally a hundred parcels of various sizes, totaling 1500 acres, in and around Mandeville. Luckily, Cellie died during the 1990-1991 recession which had depressed land values. I spent several months compiling an accurate legal description of each parcel with any known title defects and a wetland estimate using the percentage of hydric soils (from state soil maps) in each parcel. I then hired Bennett Peters, a Hammond area land company that dealt in timber and land appraisals, to appraise her real estate. Cousin Marsha Higbee found a "competent" New Orleans estate lawyer who we hired to put my information together and file the estate in late 1991. Then we could only wait for the irs response. We had to assume we would be audited but there was always hope tht we would slip through the cracks!

Return to Top

Yucatan Hydrology & Geochemistry

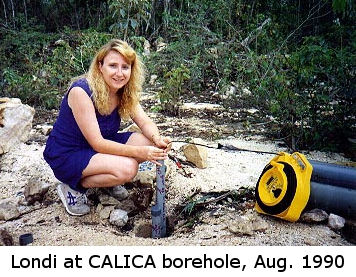

Bill's Mexican geologist friend sent a letter of introduction for me to take to CALICA management to request permission to sample groundwater on their property. I needed to do a reconnaissance of CALICA property and asked Ida to come along in the summer of 1989 to see that portion of the Caribbean. The previous year (1988) category 5 Hurricane Gilbert had crossed the northeastern Yucatan Peninsula and the coast was unrecognizable with many buildings destroyed and all of the coastal coconut palms gone. We showed up at CALICA's main office and gave my letter of introduction to John Clark the plant manager. He was a tall, thin, wiry geologist who looked at my reference letter, looked at me, and said "I hate that son-of-a-bitch." This was not a good start! I needed to make amends. I replied "I don't know the bastard but he was the only one we had to contact." John looked at me warily and smiled. I explained my geochemical research and talked about my experiences doing field work in the Yucatan and Guatemala. I probably threw in my East Africa experiences for good measure. He was worried my results might be used by environmentalists against the company in the future, and I was telling him that they could be useful in planning their mining operations. We had something in common. He too had once been captured, only his experience sounded more life threatening than mine in Guatemala. He was kidnapped at gunpoint in Mexico City along with an associate, shoved into the trunk of a vehicle, and driven around the city for hours. Eventually the vehicle stopped to let them out to pee. He decided there was no way he was getting back in that trunk. He just walked away to freedom while his captors yelled and threatened to shoot and his associate pleaded with him to come back. They didn't shoot. The guy was tough. John finally told me "OK, I'll send an employee with you to look around the property and then let me know what you want to do."

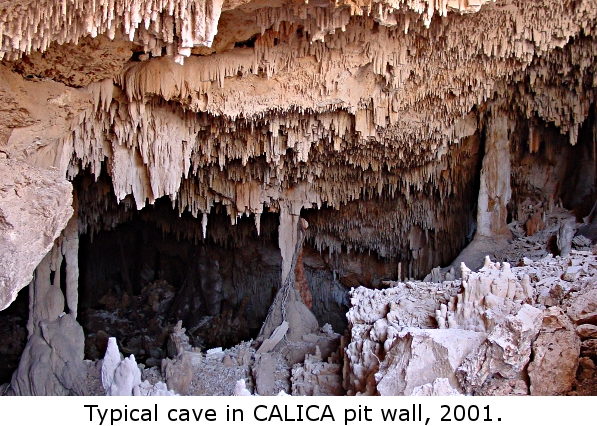

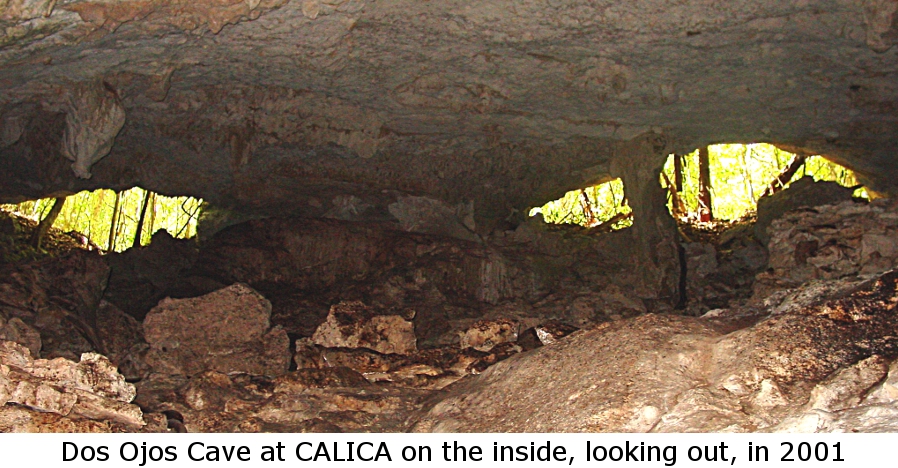

Tucked away on one corner of the SW corner of the property, in the jungle, were two sinkholes (cenotes) reached by short hikes through the jungle. I named them Little Calica and Big Calica. They were both about two hundred feet across with Little Calica somewhat smaller. Both had vertical sides down to the water table, about 40 feet below.

Back at CALICA's main office, I asked John Clark to use his drilling rigs to drill a series of boreholes along the roads leading to the open pit. The boreholes needed to pass through the freshwater lense into the underlying salt water. I intended to bring graduate students back the next summer to sample the water in the boreholes as a function of depth and do the same in Little Calica and Big Calica. And John agreed to have the boreholes ready when we came back in 1990. At the time I did not yet know Londi Moore so this was for geochemical research only. However, by 1990 the project had expanded to include geohydrology which became her MS thesis.

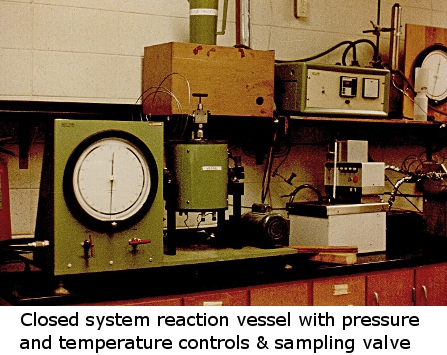

Back at UNO in the early spring of 1990, I was going out with Londi Moore, Dale Easley's graduate student in geohydrology. One weekend Londi asked me to go with her and Dale to her field area at Golden Meadow in South Louisiana. She was going to model groundwater flow around an old oil field that had become polluted from the surface disposal of produced reservoir brines. At first glance, the field area looked like a scene out of Dante's Inferno. The ground was yellow with sulfer from hydrogen sulfide oxidation. If it wasn't a superfund site, it would soon be. I told her about the beautiful green waters of the Caribbean and suggested she come work in the Yucatan on groundwater flow. Dale was not happy, but he would still be her major professor, and I could help her with her field work. I could not serve on her M.S. committee for obvious personal reasons. At the same time, two Chinese students had enrolled at UNO to work with me in geochemistry for their M.S. degrees. They had brought their wives with them from mainland China. One of them (Yang Chen) was doing a laboratory diagenesis thesis on low-Mg calcite with my flow-through reaction vessel, and the other (Yong Chen - no relation to Yang) was going to work on the water chemistry in the boreholes at CALICA in the Yucatan. Yang wanted to visit the Yucatan and he accompanied us (to help Yong in the field) during August, 1990. I remember Yong telling me that in China, professors were viewed as a father figure to students. I couldn't live up to that but Londi did her best to take care of them. At the start of the previous fall semester, she had taken all of the new foreign students on a French Quarter tour. She accidently brought the group into a well-known gay bar for drinks. "Hmm - Wow - America is really different."

Return to Top

Londi in Europe and our Wedding

Following Cellie's death, Londi and I went back to the Yucatan in May for more field work.

Teaching at the summer program was different for me this summer. I had done it before and knew the ropes. The administrators acted like heads of state and had the students and faculty marching around in parades, but the class schedules were not adjusted to the needs of the students. Who were they trying to impress? I had no respect for them and (as a full professor) simply ignored them which caused some irritation. They complained I was unmarried and living with a UNO graduate student (Londi), thereby setting a bad example. Since the head administrator was bisexual, living openly with her partners, I replied they needed to get a life and grow up. The administrator chief assistant and I almost came to blows when he tried to bully me. Obviously I was not interested in returning to teach there again, which was true.

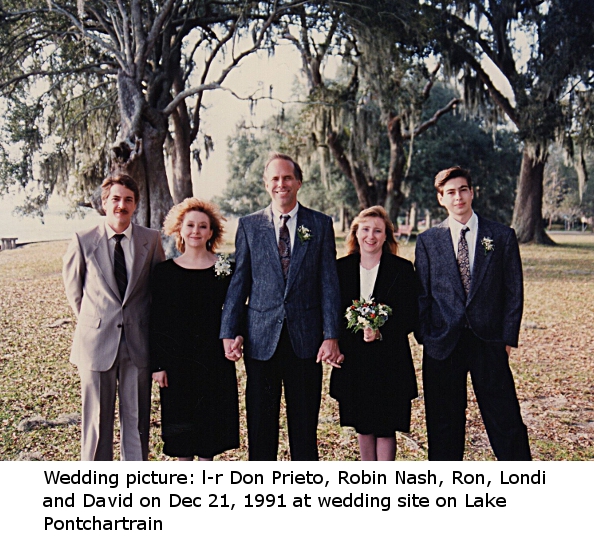

Back in Louisiana, Londi MS thesis research on

coastal Yucatan groundwater flow was accepted for publication in Ground Water. So when she defended her thesis, it was already "in press", very impressive. She graduated from UNO with her M.S. in Geohydrology in 1991. After our summer in Innsbruch, Londi accepted a job as a hydrologist with URS, a consulting environmental engineering firm in New Orleans. She enjoyed the work but not the "sexism" of the company management. We were married in Mandeville on December 21st under the live oaks on the Lake Pontchartrain Lakefront by a defrocked Catholic Priest (Mike Zimmerman) - very appropriate I thought. Robin Nash, Londi's old friend in Shreveport, had recently moved to Mandeville and was her maid of honor. Robin later married Miles Gautreaux whose family had moved from Houma and Londi knew them while growing up there. David was my best man and of course he and his partner in crime Ryan McClendon got totally smashed at the reception dinner at the Pontchartrain Yacht Club. It was a good way to end 1991, a year that had sadly begun with Cellie's death.